Previous - Portrait of Sun Yat-sen

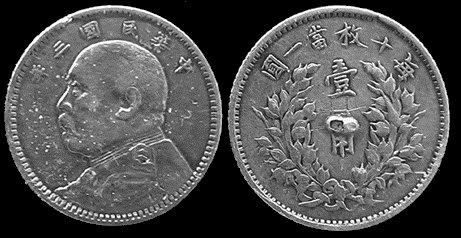

Portraits of Yuan Shikai on Chinese coins

On November 14, 1908, the penultimate emperor of the Qing

Dynasty, Guangxu, passed away at the age of 37. Various rumors were spread about

his death.

The last emperor Pu Yi in his book "The First Half of My Life" made the

following assumption: "... Guangxu was completely healthy the day before his

death. His health worsened after he took medicine. Only later did it become

known that this medicine was sent by Yuan Shikai... According to some sources,

Yuan Shikai bribed the doctor, giving him 33 thousand dollars, and he resorted

to poison."

It is known that Guangxu considered Yuan Shikai so loyal that he allegedly gave

him a secret order to execute the governor of the capital province Rong Lu and

other supporters of Cixi. Yuan Shikai chickened out and showed the order to Rong

Lu himself, and he told everything to the Dowager Empress.

So, fearing for his life, Yuan could well have poisoned the emperor.

It is also true that there is an assumption that Cixi herself was to blame for

Guangxu's death, as she died the day after his death. Shortly before her death,

she ordered the execution of Yuan Shikai, but he somehow managed to escape.

So by the beginning of the revolution, the general already had considerable

experience in political intrigue. After Cixi's death, power passed to the last

emperor Pu Yi, who was only two years old at the time. Prince Chun, who was

appointed regent under him, removed Yuan from all posts and sent him from

Beijing to his native province of Henan.

However, Yuan soon again entered the political arena. Thus, on October 27, 1911,

i.e. two weeks after the beginning of the revolution, he appeared at the head of

punitive troops in Beijing, where he received the post of prime minister and

secured the full support of the Qing court in the fight against the revolution.

At the same time, he manages to contact the leaders of the revolutionary south.

In mid-December, negotiations between representatives of the Qing government and

the revolutionaries begin in Shanghai, and on December 25, Sun Yat-sen arrives

there and is elected by an absolute majority of votes as interim president of

the Chinese Republic. Sun immediately sends a telegram to Yuan Shikai, informing

him that he is accepting the presidential post temporarily and is ready to cede

it.

Further events unfold with kaleidoscopic speed. On January 1, 1912, in Nanjing,

Sun takes the oath, proclaims the Republic, and at the end of January, the first

Chinese parliament, the National Assembly (Canquan), is created. Following this,

on February 12, an edict is issued on the abolition of the monarchy, and on

March 10, the first democratic constitution of the Chinese Republic is adopted.

Interestingly, the edict on the abolition of the monarchy also approved a

republican form of government, but... under the presidency of Yuan Shikai.

In accordance with this, Sun Yat-sen transfers his powers to Yuan Shikai and on

February 15, 1912, at the age of 54, the general becomes provisional president,

and on March 2, his inauguration ceremony takes place.

In August 1912, Sun creates the National Party (Kuomintang), which receives a

majority of seats in both houses of parliament. This does not suit Yuan and he

begins to fight the revolutionary forces. By September 1913, he manages to break

the resistance of the Kuomintang and he achieves a decision from parliament to

extend his powers indefinitely.

Now Yuan proceeds to the next step - the dispersal of the Kuomintang. Since the

necessary quorum is missing in parliament after the arrest of members of this

party, Yuan also dissolves parliament on January 10, 1914. By May, the general

introduces an amendment to the constitution, regarding a life-long presidential

term and the right of the president to appoint his own successor.

Yuan Shikai's moment of glory was approaching, and he

ordered the issue of coins with his portrait.

The preparation of the dies was ordered from the Italian engraver Luigi Giorgi,

who lived permanently in Tianjin, where the Central Mint was located. Giorgi had

a rather mediocre photograph of Yuan, in which he looked frail and timid. Using

this photograph, Giorgi prepared a sketch of the dies.

However, when he met the general in person, he realized how much this sketch

differed from the original. In front of him sat a man of a dense build, with a

massive head set on a strong neck and a heavy look.

Giorgi had to urgently make a new portrait, which ended up on the obverse of the

first republican coins.

The one dollar coins were minted in gold and silver at the Tianjin Mint and were

dedicated to the founding of the Chinese Republic under the presidency of Yuan

Shikai.

The obverse of the coins features a portrait of a general in uniform and a

feathered military leader's cap. On the reverse, at the top, is the inscription

in Chinese "Foundation of the Republic", in the center, in a wreath of rice

ears, and at the bottom, the denomination in Chinese and English ("Yi yuan" and

"One Dollar").

The gold coins were not intended for circulation, but were used for presentation

purposes.

On some of the trial silver coins, the engraver placed his first and last name

"L.GIORGI".

Trial coins minted in copper are known. It should be noted that the first coins

in honor of the founding of the Chinese Republic were already issued in 1912,

and their obverse featured a portrait of Sun Yat-sen. But Yuan Shikai really

wanted to look like the founder of the republic.

In the same year of 1912, a trial copper coin of 10 fen denomination was issued

with a portrait of the general president.

One dollar. Yuan Shikai, silver, 1914

At the very end of 1914, silver coins of 1 dollar (yuan),

50, 20 and 10 cents (5, 2 and 1 jiao) were issued into circulation.

A gold coin of 5 dollars was also minted. The reverse of the coin depicted a

dragon in the clouds (Fig. 64). This coin is considered to be very rare. A trial

version of a 5-cent coin with the same type of portrait, but in bronze, is

known, but it was not issued in large quantities.

One Dollar Yuan Shikai Silver First Issue 1914

5 jiao (50 cents) Yuan Shikai Silver First Issue 1914

2 jiao (20 cents) Yuan Shikai Silver First Issue 1914

1 jiao (10 cents) Yuan Shikai Silver First Issue 1914

The dollar coin of this issue was called by the Chinese "fat

man" or "big head" (in contrast to the dollar with the portrait of Sun Yat-sen,

known as the "small head"). However, the Chinese claim that Yuan was not as fat

as the engraver depicted him.

Dollar coins were minted from high-grade silver (0.890), the other denominations

from low-grade silver (0.700). The weight of one-dollar coins, taking into

account the tolerance, was 26.7 26.9 g. The dies were cut by the same L. Giorgi.

Dollar coins were minted in huge print runs, since the exchange of imperial

"draconian" dollars in the hands of the population for new republican ones was

to be carried out.

On the obverse of all coins there was a portrait of Yuan Shikai in profile in a

uniform and without a cap. At the top is the inscription in Chinese "Zhung guo

min ho... nian", i.e. "The Republic of China such and such a year".

On the reverse is the Chinese designation of the denomination in a wreath. In

addition, on the reverse of the coins of lower denominations at the top there

was a Chinese inscription explaining how many coins of a given denomination make

up one dollar (2, 5 or 10 coins).

The minting of coins began in 1914 at the Central Mint in Tianjin. Finished dies

were sent to provincial mints, over time they were subjected to re-engraving or

even new ones were made, which explains the huge number of varieties of the

one-dollar coin.

Thus, E. Kann counts more than 200 varieties.

The coins minted at the Central Mint maintained the standard in terms of

ligature composition and weight (or rather, they tried to maintain it), which

cannot be said about provincial issues. In addition, different mints often re-striked

coins with the earliest date (Year 3 of the Republic).

Yuan Shikai Dollar Mints

The following table gives an idea of the time and

geography of the minting of the first standard issue dollar coins bearing the

portrait of Yuan Shikai (partially based on data from the RNJ Wright Research

Collection of Chinese Coins, 1888–1949):

| Mint, Province | Years of Minting |

| Tianjin, Zhili | 1914–28 (3, 8, 9, 10) |

| Hankou, Hubei | 1921–28 (all years) |

| Nanjing, Jiangsu | 1915–27 (date 3) |

| Wuchang, Hubei | 1916; 1920–28 (date 9) |

| Mukden, Liaoning | 1926–29 (date 3) |

| Lanzhou, Gansu | 1930 1935 |

| Anqing, Anhui | 1919–24 (date 8) |

| Hangzhou, Zhejiang | 1920–24 (date 8) |

| Canton, Guangdong | 1949 (date 3) |

| Chengdu, Sichuan | 1950 (date 3) |

Lower denomination coins were also minted at the Tianjin Mint, and 50 and 20

cents were also minted at the Fuzhou City Mint (Fujiang Province).

The 50-cent coin was issued only in the 3rd year of the Republic (1914) and is

quite rare. At auctions, these coins sell for significantly more than their

dollar face value.

The 20-cent coin was issued in the 3rd, 5th, and 9th years. (1914, 1916, 1920).

It is interesting that the 10-cent coin was minted annually from 1914 to 1923,

but always with the date of the 3rd year of the Republic. A total of 7,893,249

coins of this denomination were minted. Only a part of the ten-cent coins of the

1916 issue were minted with the date of the 5th year and they are extremely

rare.

The question arises, are there any differences in the designs of the stamps, or

in other characteristics of the coins that would allow identifying the mint? We

will answer right away that there are no officially recognized ones. At the same

time, there are differences in the writing and thickness of the hieroglyphs, as

well as additional symbols on the coins, which, according to some numismatists,

serve as distinctive features of the coinage at a certain mint. However, a

serious analysis of most of these differences does not allow us to consider them

as signs of the coin's belonging to a particular provincial mint. More often,

such statements come from Chinese dealers themselves, who, for example, say that

the coin was minted in Gansu Province because his grandfather, from whom he got

the coin, told him that it was from Gansu...

For example, on the reverse of some of the one-dollar coins, in the loop of the

bow that ties the framing ears of grain, you can see a small circle (Fig. 65).

This is the so-called "variation with a circle". Many are inclined to take this

circle as a sign of the Tianjin mint, but it is unclear why this symbol is found

only on some of the coins of the Tianjin issue.

I am more impressed by the point of view according to which these coins were

minted when the communists came to power, in 1949, and quickly went out of

circulation.

The so-called "Gansu dollar" (Lanzhou mint) has more definite features, since on

the obverse of the first issues, to the right and left of the portrait of Yuan,

there are two hieroglyphs (Gan and Su), i.e. the name of the province. Later,

the hieroglyphs with the name of the province were removed from the stamp, but

some signs of provincial minting remained: differences in calligraphy and in the

thickness of the hieroglyphs, as well as in the size and some features of the

portrait (larger portrait, the presence of a fold on the upper eyelid). These

coins were minted from low-grade silver.

There is an assumption that in 1950, the mint in Chengdu (Sichuan Province)

issued coins intended for payments to workers in Tibet (the so-called Tibetan

issue). The distinctive features of the Sichuan coinage are the characteristic

triangular shape of the upper part of the hieroglyph "yuan", denoting the

denomination.

It is believed that coins minted in Anqing and Hangzhou can be distinguished by

their shallow "square" edge. Once again, I would like to emphasize that all of

the listed features cannot serve as absolute signs of minting at a certain mint,

but can be the result of re-engraving the same dies.

Now about the trial coins of the first standard issue. There is a one-dollar

coin minted in copper with an unusual type of edge, a 50-cent coin in gold for

presentation purposes, and a silver twenty-cent coin with an unapproved version

of the coat of arms of the Republic of China on the reverse. Incidentally, coins

of other denominations were also issued with the same coat of arms, but without

the portrait of Yuan.

A trial dollar was issued with a portrait of Yuan Shikai, executed from a

different angle. Instead of a pompous general, filled with a sense of his own

superiority, a tired old man with a wise peasant face looks at you from the

coin.

These coins are quite common at auctions and go for about 6-7 thousand dollars.

Trial silver dollars with the signature "L.CIORGI" are also often found.

"The Emperor" Yuan Shikai

As time went on, Yuan Shikai's appetite grew. On December

23, 1914, the general, dressed in imperial robes, performed a sacrificial

ceremony at the Temple of Heaven in Beijing, which was usually considered the

emperor's prerogative.

Yuan believed that he had every right to the throne, since he was supposedly a

descendant of one of the Ming Dynasty emperors by birth. To this end, he began

working with the provincial administration so that people would ask him to

accept the imperial title.

Naturally, he began receiving numerous petitions reflecting the "unanimous

opinion of the people."

On December 12, 1915, Yuan announced that a new era of Hong Sen's rule would

begin on January 1, 1916, and began preparing for his accession to the throne.

Special gold and silver coins were issued (although they can also be considered

medals). The same obverse die was used as for the "Foundation of the Republic"

dollar coins, and the reverse featured a flying dragon clutching a bundle of

fire arrows in its paw. The inscription "First Year of Hong Sen" was placed

below. A gold coin of 5 dollars was also minted, but with a different type of

portrait.

One dollar. Yuan Shikai, silver, 1915

Officially, coin-type tokens with the image of the emperor

in ceremonial attire and on a horse were minted from silver. By the way, there

are many counterfeits of these tokens.

However, all the coronation events could not suppress the wave of protest of the

population. Mass uprisings began in Yunnan and other provinces. The attitude of

the people towards the future emperor noticeably worsened after he agreed with

the predatory territorial and political claims against China, put forward by

Japan in connection with the beginning of the First World War.

It was necessary to wait with the adoption of the title, and at the end of March

the 83-day period of the reign of the new Emperor ingloriously ends.

Yuan himself remains president for now, but fleeing from the protest of the

population, he leaves for his province, where on June 6, 1916, according to the

official report, he dies of uremia. According to other information, the general

himself took poison (or maybe he was poisoned, which was always the case in

China).

With the death of Yuan Shikai, the issue of coins with his portrait did not

stop. Silver dollar coins continued to be minted in China even under the

communists, although the silver content in them did not reach the standard.

It is known that in 1919, dollars with a portrait of Yuan Shikai were minted in

the "proof" category at one of the mints in Great Britain.

In 1919, China also issued bank gold coins in denominations of 10 and 20

dollars.