Portraits of Chinese Emperors on Coins

A Brief History of Coins in China

The first real coins appeared in China, probably in the 8th

century BC. Before that, cowrie shells, turtle shells, silk, and

grain served as objects that replaced them in trade

transactions. With the advent of advanced bronze casting

technology, coins of various types and shapes began to be cast -

thus, there were coins in the form of knives, rings, shovels,

hoes, musical plates, and bells. Over time, round coins with a

square hole in the center (錢 - qian) replaced all others.

After

the unification of China during the Qin Dynasty (221-205 BC),

Emperor Shi Huang Di issued a decree on the confiscation and remelting of all coins of non-standard shape. Instead, the

aforementioned round coins with a square hole were issued.

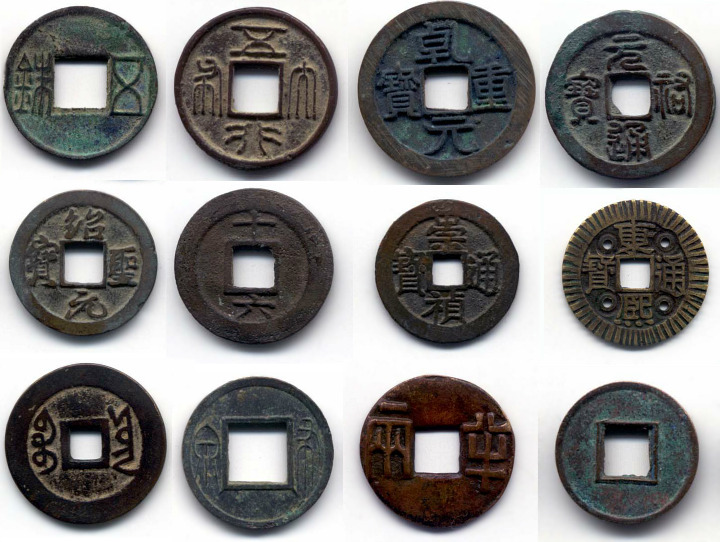

Cast coins (qian)

Qian were cast from bronze, very rarely from copper, brass, or iron. This type of coin existed for over 2,500 years, setting a kind of record, and it was only in 1889 that China abandoned them. A new coinage system was adopted based on the Mexican dollar (peso). One dollar (圓 "yuan") was equal to 10 jiao (毫 or 角), or 100 cents (分 "fen").

Portraits on Chinese Coins

As in other Asian countries, imperial China was prohibited

from depicting portraits of the emperor and important state officials on

official issues of coins, medals/tokens (both terms will be used interchangeably

in this text). Therefore, portraits first appeared only after the revolution of

1911, as a result of which the thousand-year empire became a presidential

republic.

The turbulent history of Republican China brought many political figures of

various persuasions to the historical arena – from supporters of the restoration

of the monarchy to adherents of the national version of orthodox Marxism.

Individual provinces of a large and very diverse country periodically fell under

the rule of local military separatists, each of whom considered himself the true

"savior of the nation" and the only contender for the post of head of state.

Naturally, each of them, first of all, tried to immortalize his image on coins

and medals. Before us, a whole string of both legally elected and

self-proclaimed presidents, local kings in the person of military governors of

provinces and military dictators of all-Chinese scale pass.

Most of the coins with the image of Chinese statesmen of the Republican period

are rare and very rare and their price reaches tens of thousands of dollars or

even more. Even rarer are genuine medals that were issued in limited editions.

Official portrait coins of the Republican period usually featured the image of

the current president. Sometimes part of the print run was minted in gold and

was intended mainly for presentation purposes. These coins are sometimes

difficult to distinguish from similar-looking commemorative medals or tokens. As

a rule, medals do not have a denomination, although sometimes it is not

indicated on coins either. However, some numismatists, even when indicating a

denomination, consider such coins to be medals (as so-called award coins) and,

conversely, classify some clearly medal-like items as coins. This is explained

by the fact that silver medals were minted on circles that, as a rule,

corresponded in size and weight to a dollar coin.

In China, the issue of so-called fantasy coins and medals was also widely

practiced, including those made of precious metals. Most of them featured images

of military governors of a particular province, the so-called wŭjūn (武軍). As a rule, these items were minted at state mints by order of the

wujun themselves. Such coins were never in circulation. Like medals, they were

mainly intended for presentation purposes during various ceremonial events,

although some could simply be the fruit of the imagination of Chinese artisans,

which is always noticeable by the quality of execution.

In English-language literature, the term "unusual coins" has firmly established

itself for them, i.e. "strange coins". Many numismatists collect such fantasy

coins and medals, they are put up for auction worldwide and prices for them

reach the same value as for official issues, or even more. Naturally, fantasy

coins and medals were minted in extremely small print runs. Most European

collectors do not have access to mint records, and English language catalogues

of Chinese coins do not always provide full minting details for proof and fancy

issues. As a result, fancy coins are sometimes mistaken for proofs and vice

versa.

Finally, we should not forget about the existence of many modern counterfeits of

both official coins and medals and fantasy issues. Sometimes such counterfeits

are difficult to distinguish from the original. In this review, the main focus

will be on regular issues of coins and medals, as well as their trial samples.

We will also address the most interesting fantasy coins and medals with images

of statesmen.

Coin issues of the last years of the empire

Coins with the image of the imperators

As mentioned above, the person of the emperor in ancient

China was considered sacred and the creation of his portraits or sculptures was

strictly prohibited. That is why it is unlikely that the obverse of the Sichuan

(or Tibetan) rupee, first issued in 1905, depicts the penultimate emperor

Zaitian, better known under the motto of Guangxu (1875-1908). Coins and tokens

with portraits of the emperor and the statesmen of the empire were most likely

minted after the revolution.

The accession to the throne of Emperor Guangxu was preceded by a whole chain of

events that took place in the palace in the second half of the 19th century.

During the reign of Emperor Yizhu (Xianfeng, 1851-1862), a beautiful concubine

with the poetic name of Little or Jade Orchid appears in the palace. This name

was given to her at birth. As the girl grew older, she was called Cixi (慈禧,

"Happiness and Compassion"). After the death of the emperor, a decree was issued

according to which both the emperor's widow Ci'an and concubine Cixi received

the title of "empress dowager" and were regents for the minor heir Zaichun (Tongzhi),

who was the son of Cixi and Emperor Xianfeng.

In 1875, the very young emperor died of smallpox. After that, in 1881, Ci'an

suddenly died (as you might guess, not without Cixi's participation), and the

"Dowager Empress" ruled alone. She managed to raise her nephew Zaitian, who was

4 years old at the time, to the throne. He began to rule under the motto Guangxu

(Glorious Heritage).

Emperor Guangxu was a weak, indecisive, and too soft a man for an emperor. He

was much more interested in the achievements of Western technology than in state

affairs, and in general showed too much interest in the civilization of guizi

(鬼子, "overseas devils"), which was completely uncharacteristic for a Chinese of

that time, not to mention an emperor. It is therefore not surprising that he was

effectively removed from power and the cruel and treacherous Cixi, who was

respectfully called "Old Buddha" in the palace, was in charge. It is possible

that she poisoned Guangxu, who died in 1908 at the age of 37. No coins or medals

with images of Guangxu and Cixi were minted during their lifetime. After their

deaths, commemorative (fantasy) tokens made of copper and light metal with a

portrait of the emperor were unofficially issued.

On the back of the tokens was the inscription: 光緒皇帝造使 "Made in memory of Emperor

Guangxu".

Commemorative token. Emperor Guangxu, copper, silver

The death of Cixi, who died one day after the emperor, was also commemorated with a token on the front of which was her portrait and the dates (1861–1908) with the inscription above: 大清國慈禧皇太后 "The country of the Great Qing to the Empress Dowager Cixi".

Commemorative token. Empress Dowager Cixi, copper, 1908(?)

Just before his death, Cixi managed to put another of his

nephews, two-year-old Pu Yi (Xuantong, 1908), on the throne. His reign was not

destined to last long - in 1911, a revolution occurred and he abdicated the

throne the following year.

Pu Yi escaped the fate of the deposed monarchs - he was not executed or even

imprisoned, he continued to live peacefully in China. Moreover, he became

emperor again twice: in 1917, although only for 12 days, and in 1932, at the

head of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo (1932-1945).

During the war with Japan, in 1945, Pu Yi was captured by Soviet troops and

spent some time in a Siberian camp. However, after the communists came to power

in China, he was interned in the PRC, where he ended his life working as a

gardener.

In honor of the last Qing emperor, coins of 10, 20, 50 cents and 1 dollar were

issued in Yunnan province with his portrait. If the assumption that they were

minted in the period 1908-1911 is correct, then these are the first coins issued

with a lifetime portrait of the emperor. Coins of different denominations differ

only in size.

On the obverse, Pu Yi is depicted as a two-year-old baby, on the reverse at the

bottom there is an inscription in Chinese 宣統年造 "Minded during the reign of

(Emperor) Xuantong" and the name of the province in English YUN – NAN. This

issue of coins belongs to the unofficial fantasy.

Coin (Yunnan Province). Emperor Xuantong

Coins with images of statesmen

Of interest is the silver coin in memory of the outstanding

statesman of the Chinese Empire Li Hongzhang (1823-1901). He was an influential

and rich man in China, who actually served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

In May 1896, during a visit to Russia on the occasion of the coronation of

Nicholas II, Li Hongzhang negotiated with the Minister of Finance, Count S. Yu.

Witte. The negotiations concerned the construction by Russia of a railway

running through China, i.e. the future CER. Li Hongzhang's consent cost Russia

about 3 million gold rubles.

The coin's denomination is indicated in the tael system: on the reverse is an

image of the hieroglyph "longevity" framed by two dragons and above it the

designation 两壹 "one tael". On the obverse is a portrait of Li Hongzhang and the

inscription 紀念章鴻李 "In memory of Li Hongzhang". This is also a fantasy coin,

which was sold at the last auction of Ponterio & Associates Hong Kong for almost

$1,000.

Tael with a portrait of Li Hongzhang, silver

The second part - Sun Yat-sen on Chinese coins